Now hiring? The UK's workforce woes

With all the doom and gloom about the UK economy over the past four years, it may be surprising to learn that the labour market has been highly resilient. Indeed, one of the most prominent features of the post-Covid recovery has been a record-low unemployment rate1 with many employers finding it difficult to satisfy their staffing needs. However, this strength masked some important challenges, namely an increase in the number of economically inactive people combined with an aging population. This in turn led to higher wage growth and lower productivity gains in the UK as compared to peer economies, fuelling high inflation and suppressing overall economic growth. The good news is that the UK economy could finally be turning a corner on both wage growth and inflation, allowing the Bank of England to cut interest rates. However, by how much and for how long will largely depend on how the labour market tensions develop. An environment of lower interest rate and strengthening economy growth should bolster UK companies’ profit margin and in turn the UK equity market.

The UK’s shrinking pool of available workers stands out amongst peers

The labour market can be broken down into three categories:

1) people in employment (employed or self-employed),

2) unemployed people and,

3) economically inactive people2 (mostly students, retired, people who have not been seeking work within the last four weeks or are unable to work over the next two weeks, for instance for family reasons or due to sickness). The sum of employed and unemployed people is called the labour force participation rate, which can also be described as the share of the working-age population (defined as people aged 15 to 65) that is able and willing to work.

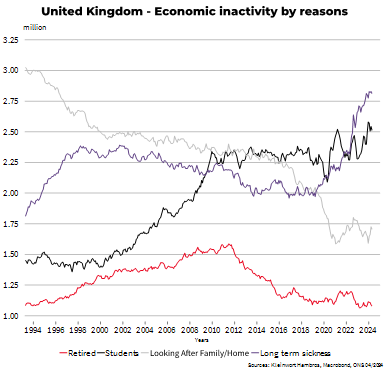

While Covid affected every country around the world, the UK economy is relatively unique in the way its labour market has shifted since then. Indeed, the UK inactivity rate (i.e., share of people not working and not looking for a job) has increased over the past four years, both in absolute terms and as compared to most of the UK’s trading partners. As a result, the pool of available workers has shrunk in the UK, exacerbating tensions in the labour market.

Demographics are problematic

The first reason for the decline in the labour force participation rate lies with demographics. Similar to most other developed (and emerging) economies, the UK’s population is aging. As a result, more and more people are dropping out of the labour force as they get older and retire. This reduces the sheer number of people able and willing to work.

But, aging also reduces the participation rate when people under 65 decides to retire early. This is especially the case for the UK, as private pensions can be claimed from the age of 55, likely leading to people voluntarily dropping out of the workforce earlier than otherwise.

Long-term sickness adds to the mix

Meanwhile, the UK has been facing a rising trend of economically inactive people due to long-term sickness and disability. Up to 2.8 million people are now outside the workforce for that reason, an increase of 700,000 since Covid3. Similarly, the UK has seen an increase in people temporarily off sick and a decrease in the overall number of working hours – dragging down UK productivity growth.

This has been partly offset by a reduction in the portion of people looking after their family or household, as remote working has allowed many people to (re)enter the labour force, and companies are increasingly accommodating irregular and extended working hours.

Don’t forget the elephant in the room

Although Brexit has largely disappeared from the headlines, its impact remains a reality, particularly in terms of the new restrictions it brought for hiring people from abroad. While net migration flows have remained broadly in line with their pre-Brexit average, it led to a shift from EU- to non-EU workers4, and from low-skilled to high-skilled workers, causing recruitment difficulties in sectors that rely predominantly on low-skilled labour.

Modest improvements lie ahead

Demographics, long-term sickness, and changes in labour migration help explain the tight labour market conditions and strong wage growth that the UK experienced post Covid. However, tensions have eased over the past few months. As the economy remained soft5 for a few years, companies have begun to adjust their workforce to the new reality. As a result, the unemployment has increased to 4.3%, the highest level since 2017 (excluding the artificial surge during the Covid period).

Neither demographics, health, nor Brexit-related factors are likely to disappear anytime soon. However, the new government appears ready to address the decline in the labour force, for example, with improved childcare policies, increased work incentives, and other measures to help people back into jobs.

Overall, we expect to see labour market tensions ease further over the coming months, and wage growth should moderate towards levels consistent with the Bank of England’s (BoE’s) inflation target. The BoE should be in a position to continue cutting interest rates. However, the BoE is unlikely to slash its interest rate down to the pre-Covid level. Into the end of 2024, only two cuts (estimated 0.25% each) are likely, though with the possibility for more in 2025. These modest rate cuts, combined with what looks to be a slight economic recovery, should support UK equity markets further.

Sources

1 Source: UK Office for National Statistics (18 July 2024)

2 Source: UK Office for National Statistics (18 July 2024)

3 Source: UK Office for National Statistics (18 July 2024)

4 Source: UK Office for National Statistics (23 May 2024)

5 The average annual UK economic growth has been week since Covid started, at 0.7% compared with just under 2% in the five years leading to the pandemic (Source: Office for National Statistics via Macrobond)

Disclaimers

Important information and Financial Promotion

This document is a marketing communication provided for information purposes and is not investment advice or a recommendation. It is not intended for distribution in or into the United States of America nor directly or indirectly to any U.S. person.

Investment Performance

Investments may be subject to market fluctuations and the price and value of investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up.

Limitation

Information in this document is believed to be reliable but SG Kleinwort Hambros Bank Limited does not guarantee its completeness or accuracy and it should not be relied on or acted upon without further verification.

Legal and Regulatory Information

This document is issued by SG Kleinwort Hambros Bank Limited which is authorised by the Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority and the Prudential Regulation Authority in the UK. The company is incorporated in England & Wales under number 964058 with registered office at One Bank Street, Canary Wharf, London E14 4SG. Services provided by non-UK branches of SG Kleinwort Hambros Bank Limited will be subject to the applicable local regulatory regime, which will differ in some or all respects from that of the UK. Please see the Information Documents on our website for further information: https://www.kleinworthambros.com/en/important-information.

Further information on SG Kleinwort Hambros Bank Limited and its branches including additional legal and regulatory details can be found at: www.kleinworthambros.com.

SG Kleinwort Hambros Bank Limited is part of the wealth management arm of the Societe Generale Group, Societe Generale Private Banking. Societe Generale is a French bank authorised in France by the Autorité de Contrôle Prudentiel et de Résolution, located at 61, rue Taitbout, 75436 Paris Cedex 09, and under the prudential supervision of the European Central Bank ('ECB) . It is also authorised by the Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority and the Prudential Regulation Authority.

© Copyright the Société Générale Group 2024. All rights reserved.

Compliance code CA141/July/24